From E-waste to

Contemporary Jewellery

This describes my experience of recovering precious metals from electronic waste for use in contemporary jewellery. In particular it illuminates the journey of recovering precious metals, from collecting waste to exchanging it for some gold and purifying the sample so it can be worked into some contemporary jewellery. Three new pieces of jewellery incorporating gold from this e-waste have been included in the exhibition A Hand in Nature: Art Metalwork and Jewellery at the National Museum of Ireland, Collins Barracks, Dublin from Nov 9, 2025 until 1 March, 2026. The exhibition is curated by Eva Lynch and Dr Edith Andrees and considers the impact of our use of materials on the landscape and suggests more sustainable ways of sourcing materials.

Collecting e-waste

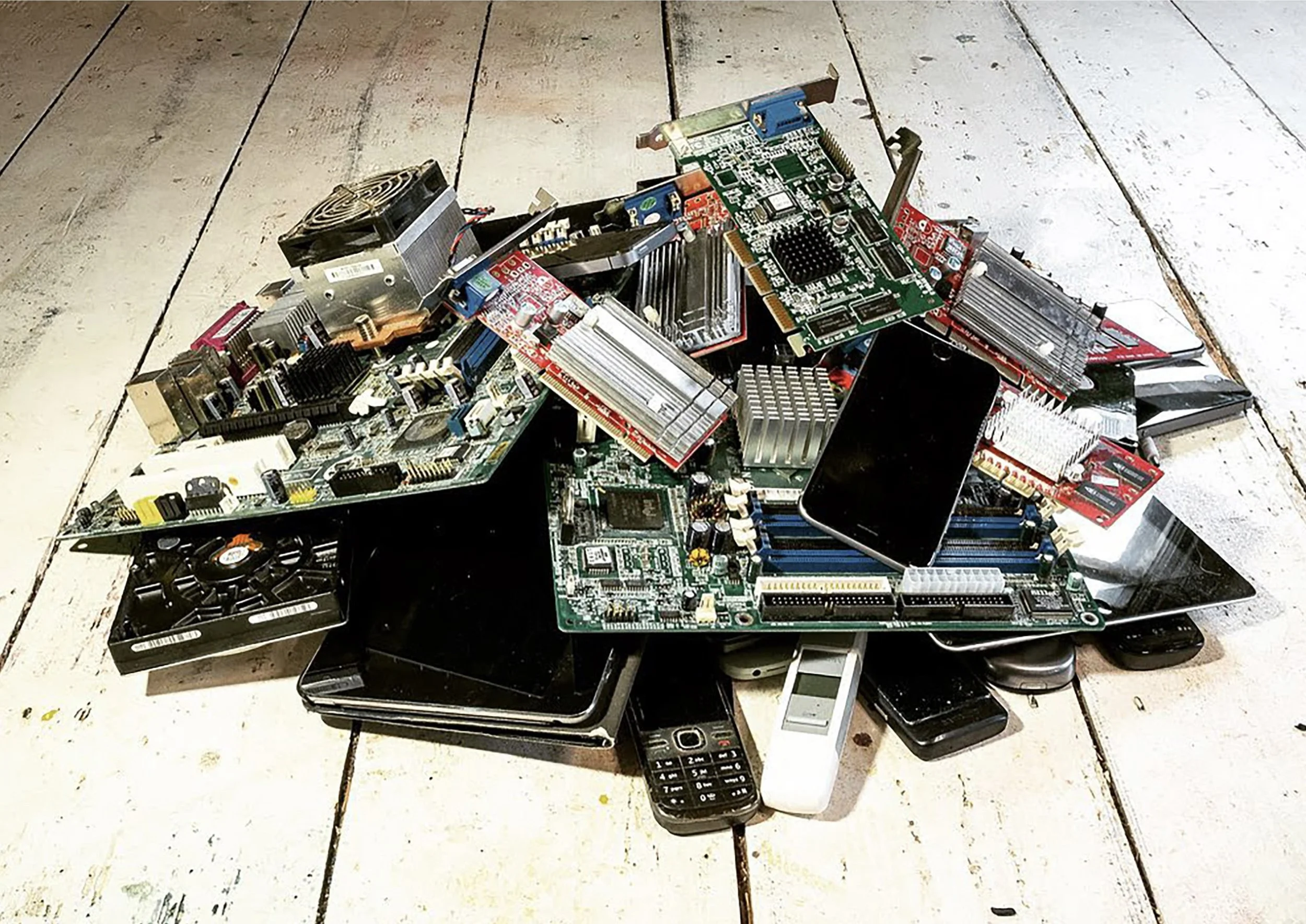

The story starts in Killeagh in 2021 during an artist residency at Greywood Arts. This is a space where artists and the community of East Cork can come together to explore the creative process, grow and connect. I had been attracted to the residency at Greywood as it focused on the creative process. During the residency in June 2021 I invited the local community to donate their old electronic waste so I could recover some precious metals for use in new contemporary jewellery. Over the course of four weeks around 20 mobile phones, 2 tablets, 14 circuit boards of various sizes and assorted cables, wires and remotes were donated.

Fungible Gold

Unfamiliar with the state of recycling in Ireland I started to contact companies hoping to find someone that might be willing to exchange this e-waste for some gold and quite quickly got a very positive response from Kurt Kyck the managing director of KMK metals in Tullamore. KMK are a metals recycling company who collect and process e-waste which is then shipped to other companies for the metal recovery process. At the end of the residency, I travelled up to Tullamore and was fortunate to be given a tour of the facility and handed a small coil of gold (2.4g) from an integrated circuit board of a computer. Presumably this was one of the very early computer models which tend to have a much higher gold content than more recent products. Mr Kyck explained to me that this gold had sat at the back of the drawer in his office for several years with him always intending to do something with it. We often hold onto our e-waste and consequently the precious metals they contain become lost to circulation. This is gold that is fungible, that is the gold in the e-waste I had collected was substituted for a gold coil considered identical to any gold that may have been recovered from my e-waste. Gold is therefore considered a fungible commodity as it can be exchanged for identical material.

Working the gold

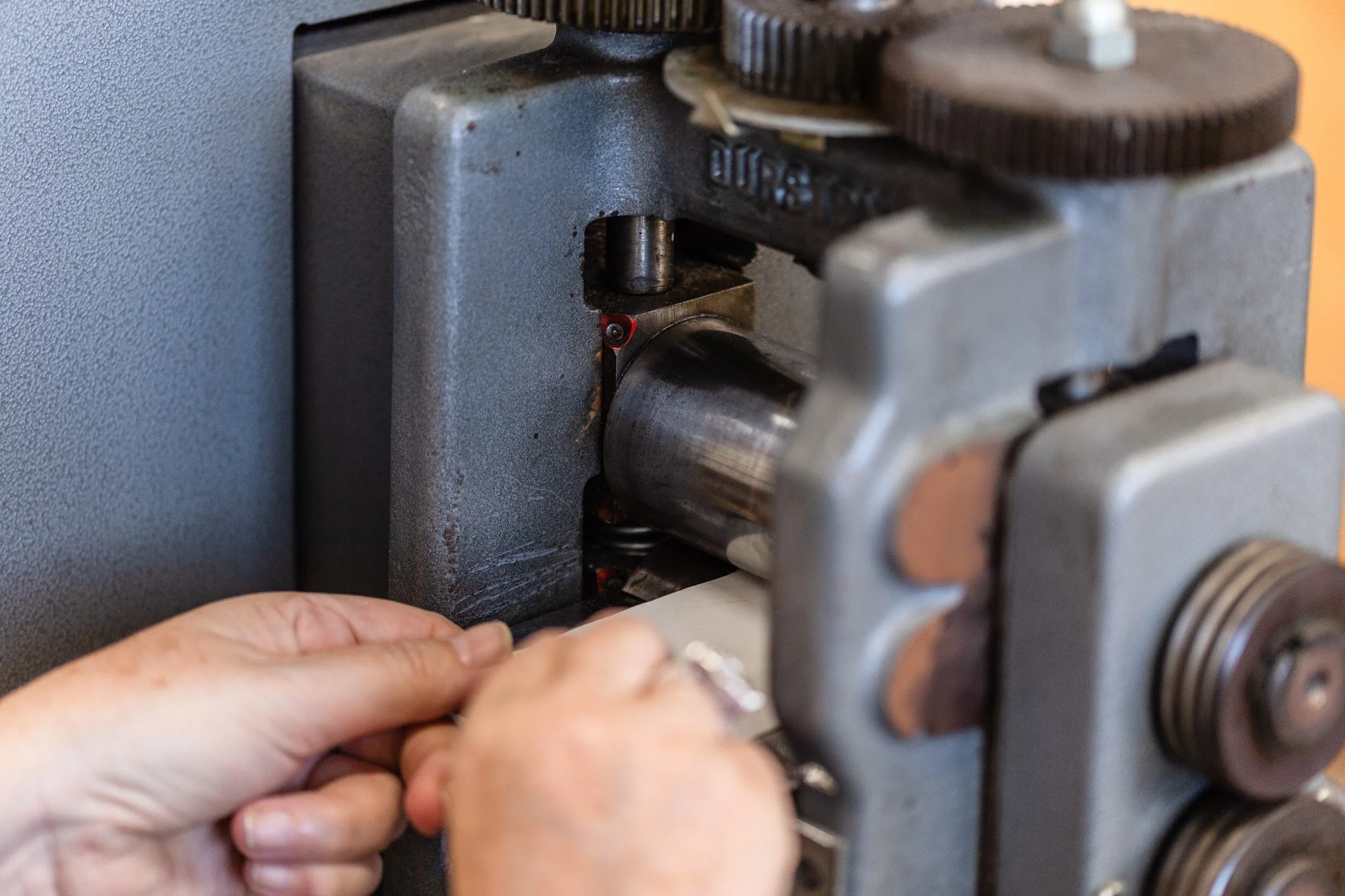

On returning to Dundee, I was keen to melt the gold down into a small ingot and roll it out into some thin foil to use in a new piece of jewellery using a metal damascening technique that is still practiced in countries such as India and Japan. I could have used this gold in its fine wire state – but I’m not sure that the coil would have unraveled without breaking into many pieces. The Damascening technique is a frugal way of working with gold as the foil is 0.02mm thick and so a little can go a long way. 2.3g of gold should roll down into a piece 0.02mm thick - 11.73 cm x 11.73cm. Given the small quantity of metal it was easier to melt the coil on a charcoal block into a small ingot at the hearth so I could then roll it down into a thin sheet. A rolling mill that looks a bit like an old mangle for washing clothes is used to progressively make a piece of sheet thinner. On starting to roll the gold down using an electric rolling mill at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design, part of the Dundee University it became clear that this was not pure gold as originally thought. The gold after just a few passes in the rolling mill had quickly started to work harden and needed to be heated again to soften the metal. A piece of pure gold is soft enough that it should be able to roll down to 0.02mm thick without any further heating and so this told me that there was something else in the this coil that was making the metal harder to work.

Testing the Gold

The Edinburgh Assay Office offers a precious metal testing and analysis service, so they can identify what other metals might be present in the sample. XRF is the most common method used as it is non-destructive and can be carried out quite quickly. The report from the Assay Office cost £50 + VAT, and it identified that the sample was 99.5% pure gold but also contained some antimony, iron and copper. Antimony is often added to gold to harden it for use in electronics which therefore made sense given this sample came from an old computer integrated circuit board. The report stated that the sample was suitable for hallmarking as 916 gold (22ct). To reach a higher purity and therefore hallmarking standard it required purifying as adding extra pure gold would not remove the impurities.

One of the biggest challenges in recovering, recycling and reusing materials is being able to identify exactly what it is that you are working with. In this case antimony also carries some risks with it and yet we had already melted it down at the hearth. In high concentrations antimony can cause problems for the lungs and heart, but thankfully we were working with a sample with very low concentration and our hearth has good extraction. So, I hope we have suffered no ill effects from this process. Surprisingly the gold when rolled had formed a heart shape – evoking the idiom ‘a heart of gold’! Could this e-waste gold be valued for its goodness?

Refining the Gold

Once we had identified exactly what the gold coil contained the next step was to remove the impurities. Project collaborators at the Love Chemistry Group at Edinburgh University purified the gold using their refining process. This is a four-stage process that involves leaching, to dissolve all the metals into solution; the chemical reduction of the dissolved gold to create an insoluable gold/ligand complex, using a ligand system designed by the University of Edinburgh; and stripping the gold from the complex, using water. The final stage is the electrowinning of the dissolved gold in the solution, to create powdered gold of high purity. In this process the 2.4g gold coil was transformed into 2.3g of pure gold powder.; 0.1g in weight being lost through purifying the coil of the copper, iron and antimony.

Gold powder is historically significant in Ireland, used in ancient Bronze Age jewellery like the famous lunulae and torcs, and in a famous 1795 gold rush in Wicklow where a large amount of gold was found in rivers. The next gold rush however is likely to be in homes and landill sites where gold rich e-waste is discarded. In India gold powder or dust as it is sometimes known also has a long history. It was first recorded in the 5th or 6th century BC as a naturally occurring powder collected by ants. This was known as pipilika gold – pipilika being the Sanskrit word for ants. This form of gold was considered a novelty and it was used for medicinal purposes and making colours for painting. For children a tonic containing gold powder was believed to improve their brain power and physical strength. You could say that metal recyclers are todays Pipilika!

We don’t however know the journey of the gold coil before it became part of an integrated computer circuit. The gold could have come from recycled old jewellery - perhaps at one stage it may have been from a Queen’s crown? Was it freshly mined gold from a fair trade mine in Africa? Had children been harmed or the environment damaged in its collection? Did it come from a gold robbery for example Brink’s-Mat and was melted down with other gold? The simple answer is that we just don’t know and this presents a problem! Consumers increasingly want to know where their gold comes from and that it is ethically sourced. Being able to track and trace the journey and ultimately the story of where the gold has come from is vitally important!

Inspiration for contemporary jewellery

As an artist working in metals, I have taken my inspiration from the shapes and patterns of electronic circuit boards. Some of these shapes have been common motifs in my previous work such as circles within circles. I hope these references to computer circuit boards are subtle and not too obvious. According to the European Chemical Society precious metals such as gold are increasingly endangered and if we continue to mine at the current rates we could run out of this significant metal in just over 100 years! I had also therefore been searching for a frugal way of working with precious metals and found damascening an ancient metalworking technique that is still practiced in different parts of the world today for example Toledo, Spain, known as Koftgari in India and nunome zogan in Japan.

Nunome Zogan

Nunome zogan translates as cloth weave or fabric inlay due to the cross hatched pattern created in the metal sheet made with chisels that resembles fabric. I first heard about nunome when I was teaching at the Penland School of Craft in North Carolina. Nunome is a meditative time-consuming technique that involves chiselling the metal creating around 8 – 10 chisel marks per mm and the metal sheet is cross hatched in four different directions. Once cross hatched the thin metal foils 0.02mm (that are hand rolled) are secured using a piece of bamboo chopstick and then burnished. This video was created at Greywood Arts to give some insight into the nunome zogan process.

Japanese Irogane Alloys

The pieces on display have been created with the Japanese alloy shibuichi (an irogane copper alloy) that is around 80% copper and 20% silver which can then be coloured using a solution made of copper sulphate, rokushu – a type of Verdigris and distilled water. This colouring solution is known as Niiro. The piece is cleaned with magnolia charcoal and boiled in the solution for around ten minutes or until the desired colour is achieved. I prefer satin finishes and so brushing with a little baking soda before colouring keeps the surface matt. When coloured the shibuichi turns a beautiful shade of grey highlighting the gold foil.

The Collection

In my design process I work with paper models to begin with and sketchbook possible design ideas before cutting my foil shapes. The ideas from my sketchbook and paper models feed into the final design with changes at every stage.

Fingers Pendant. 48mm x 55mm x 1mm. Fine gold, 18ct green gold, shibuichi, sterling silver tube, yellow Japanese kumihimo eight strand braided cord. Image: Diarmid Weir.

The twenty one yellow gold finger shapes are from e-waste and suggest the number of electronic devices that we might own in a lifetime.

Circuit board "fingers" (also called "gold fingers") are the gold-plated contact points on the edge of a printed circuit board (PCB) that are used to connect it to another board or device. This was the first piece in the collection to be made.

It is not possible to tell from sight what is gold from e-waste and what is gold from other sources. Being able to provide greater transparency over where our materials originate from is one of the biggest challenges facing the jewellery & metal design industry today. The Edinburgh Assay Office have recently introduced a new innovative ‘Smartmark’ - that enables the integration of hallmarking with wider blockchain traceability programmes and digital product passports. This enables consumers to see the full chain-of-custody tracking—from raw materials to the finished piece in the consumer’s hands—transforming hallmarking into a powerful tool for transparency and trust. As this pilot scheme is developed it will enable consumers to track and trace the journey the materials in their jewellery has taken.

One bullion dealer informed me that even gold that is described as fresh material has not necessarily come direct from a mine but rather includes maybe as much as 80% recycled material from a variety of sources including e-waste. Interestingly there has also been some debate in the jewellery industry about what terms to use, with some critical of the term ‘recycled’ seeing it as a form of greenwashing that can be misleading to consumers as it obscures complex issues in the supply chain. Repurposed is the preferred term as gold and other precious metals are so valuable they are rarely, if ever, considered a "waste” stream. Within contemporary jewellery if you met your partner online - wearing a piece with gold from e-waste may have some meaning, however for others they may have some concerns about wearing something that was once a waste product. It is hoped these contemporary jewellery pieces will spark some further debate of these issues.

Traces brooch. 51mm x 51mm x 1mm. Shibuichi, fine gold, 24ct e-waste recycled gold, 18ct green gold, gold plated copper wire and steel pin. Image: Diarmid Weir.

The five circuit board finger shapes are from gold recovered from e-waste.

In electronics a trace is a conductive pathway, typically made of copper on a printed circuit board that connects components. Traces vary in width and thickness depending on the current they need to carry.

In earlier work I utilised the solutions that were generated from recovering precious metals from electronic waste to colour and patinate the metal and in this work, I was pleased to be able to use actual gold traceable from e-waste. I was very particular about keeping the gold from e-waste separate from any other gold that I owned. Whilst, I was able to source a small quantity of gold from e-waste, for most jewellers looking for a traceable supply of precious metals this is still very difficult to access. The process of identifying and purifying if necessary is also very difficult and costly for an individual jewellery artisan. Increasingly we have seen a proliferation of new sources of gold for example, single mine origin, peace gold, recycled gold. The main difference between these supplies of gold is how the metal has been sourced and the ethics surrounding it. I was able to exchange my collection of e-waste for a piece of fungible gold that is gold that is mutually interchangeable. In a future project I am looking to create a collection of work that utilises non-fungible gold ie material that comes direct from any waste collected.

Via Pendant. 75mm x 35mm x 1mm. Shibuichi, fine gold, 18ct green gold, sterling silver, and electroplated hematite beads and recycled sterling silver. Image: Diarmid Weir. The gold circle in this pendant was refined from e-waste and rolled down to 0.02mm. In electronics, Via refers to a plated hole connecting different layers of a printed circuit board (PCB). The electronic definition comes from the Latin for "way," describing the path for electrical signals between layers.

In my design process I like to leave room for spontaneity and the unplanned for example in the Via pendant when the e-waste circle I created split which could suggest a circular economy that has fallen short of its goals.

It is hoped that the pieces in this collection raise awareness of the how much precious metals are in e-waste, the need to recover and recycle this culturally significant material and encourage people to think about where their materials come from.

Thanks to the people of Killeagh who donated their old electronic waste, namely; Maura Murphy, James Mansell, Jessica Bonenfant, Jaki Coffee, Carole Redmond, Martina Williams, Letta Hogan, Katie Higgins, Ann Rochford, and Sheila de Courcy.

Thanks also to the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) who helped fund this research as part of a bigger project exploring creating new jewellery from electronic waste. This webpage has been amended and added to from Brick, Bread and Biscuit: The Chemical Recycling of Precious Metals from E-Waste for Jewellery Design in India a book detailing some of the outcomes from this EPSRC research.